What might we in higher ed learn from the travails of Peloton (the company)?

Before diving in, the usual caveats of this sort of lateral thinking about academia apply:

- Higher education is different from other industries, and schools are not like companies.

- Higher education is a public rather than a consumer good.

- Higher education is highly regulated and broadly (if diminishingly) publicly financed.

Any lessons that we can glean from Peloton will likely have more entertainment than practical value. But that should not stop us from trying.

The headline news from Peloton is that it is a company that thrived during the pandemic only to see its fortunes diminish in recent months.

This overall story says nothing about the quality of the exercise experience on a Peloton bike (or treadmill). Many of my closest friends and colleagues own a Peloton, and they love the classes and swear by the entire experience. (My household considered a Peloton but decided to stick with our Les Mills streaming workouts.)

The Peloton story we are considering through higher ed eyes is that of the company’s recent challenges. Those challenges are best represented in the company’s stock price, which peaked at $130 a share in July 2021 and is currently trading at $22. Where the company was worth over $47 billion this past summer, today, the company has a market cap of under $10 billion.

The precipitous fall in Peloton’s stock has led to speculation that the company might be acquired. Apple and Amazon are sometimes mentioned as potential buyers. We will see.

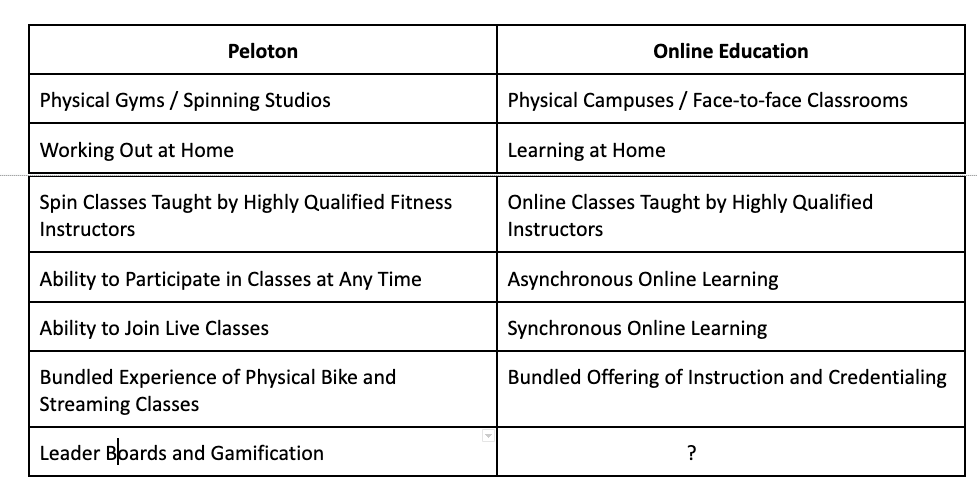

From a higher ed perspective, there are some intriguing parallels between Peloton and the fastest-growing aspect of the postsecondary sector—online education.

Assuming that we in higher ed want to avoid having our universities experiencing a similar fate as Peloton (layoffs, leadership shuffles, etc.), what can we learn from the company?

We need to separate the experience from owning and using a Peloton (which everyone—at least my friends—seems to agree is fantastic) from the experience of owning stock in Peloton. (Not so great if you bought at $130 a share.)

Peloton got in trouble not by offering a bad combination of product and service. That integration is fantastic. Peloton (or its investors) seems to have gone wrong by assuming that growth would continue indefinitely.

In retrospect, what should have been obvious was that the massive spike in demand that Peloton experienced was a function of the pandemic, as opposed to a result of longer-term and more durable trends. At some point in the last two years, most of the households with the desire and the disposable income to buy a $1,500 to $2,500 Peloton bike did so.

At the same time, it should have been clear that some portion of fitness enthusiasts would want to return to their local gyms once the pandemic receded.

Thinking that a $47 billion Peloton makes sense is like believing that everyone who shifted to remote learning in 2020 and 2021 will indefinitely stay online.

Believing that the price of Peloton could keep going up from $130 a share is like thinking that remote learning and online learning are the same.

Champions of online learning should keep in mind that future growth will be incremental.

In the future, we are likely to see faster growth in the supply of online programs (as more schools get in the game) than in demand for online learning. Colleges and universities will fight for each online enrollment. The competition in online programs, already fierce, will only become more intense.

Like Peloton, we should not assume in higher education that providing a terrific online learning experience (akin to Peloton’s superior home exercise experience) will be enough to drive never-ending growth.

Many students will prefer to learn on campus and in a physical classroom. Face-to-face learning is not going away. We need to look at online education as a complement to residential learning, not a substitute.

Growth in online education will ultimately come down to the combination of advances in both quality and costs. The fastest growth in online degrees will be in low-cost scaled programs.

Peloton has been unable to figure out how to bring the costs of their bikes down to a level that creates demand outside of affluent and hard-core exercisers. Colleges and universities will need to figure out how to offer high-quality and low-cost scaled online degree programs if they hope to grow demand for higher education significantly.

For me, the ultimate higher ed lesson of Peloton is to err on the side of underpromising and overdelivering. Peloton would have been fine if the company had been more clear-eyed about the short-term reasons for its sudden popularity and the likely business realities once the pandemic ran its course.

Those of us in the online learning world should be highly circumspect in our predictions of the future and reluctant to claim that rapid and sustained growth will be inevitable.

What do you think might be some higher ed lessons from Peloton?

More Stories

10 Questions to Ask When Considering a Health Insurance Quote

Is EFL or ESL English Teaching Practical for Home Schooling?

Non-Obamacare Short Term Health Plans On The Rise